Part 2: Good to know

The second book, Georgia, is about the stay of the Suttner couple in the distant Caucasus country. Bertha and Baron Arthur Gundaccar von Suttner eloped secretly because Arthur’s family was against their marriage. Find out whether their dreams came true in Georgia when you read this book.

Das dritte Buch „Friedensaktivistin, Bestsellerautorin, Nobelpreisträgerin“ findest du hier:

What do you learn in this book? Click here for more detailed information…

The journey to Georgia in 1876 was also an escape from Vienna for the young Suttner couple. As their marriage did not conform to the principles of upper middle-class or aristocratic society, where the husband—usually older than his wife—could support a household through his occupation or wealth. Such a notion of marriage was completely alien to peasant or artisan classes as traditional employment for spouses often came from farming or trading which were seen as equal. From the Enlightenment onwards, attempts to abolish class differences emerged in favour of a normative image that would apply to everyone. This also had an impact on the concept of marriage and was reflected in civil and private laws enacted in many European countries around 1800. For example, the Austrian General Civil Code, which had been in force since 1812, explicitly stated in paragraph 91: “The husband is the head of the family […] but it is also his duty to provide his spouse with a decent living according to his means”.

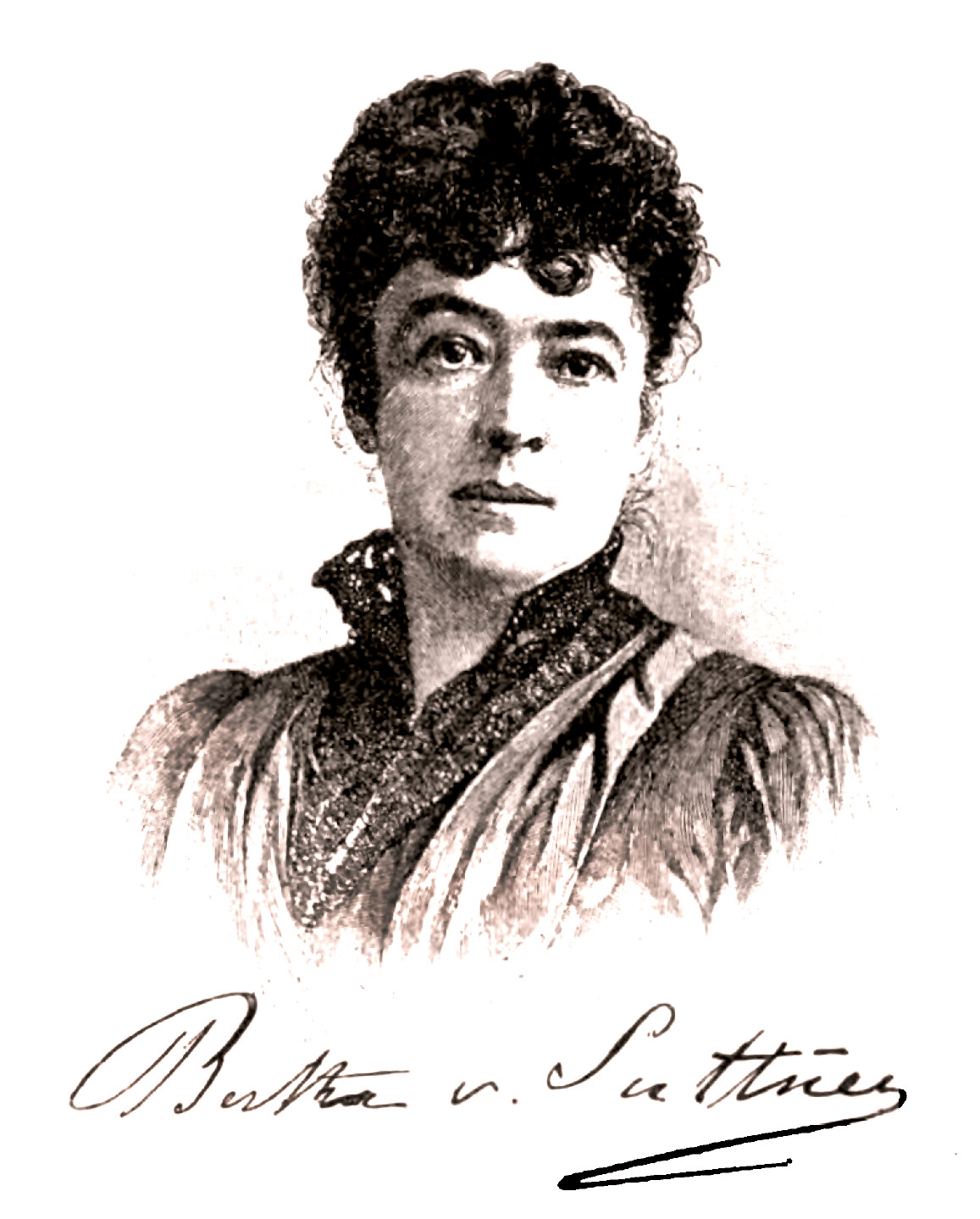

This was not the case for the twenty-six-year-old dropout Arthur Gundaccar. Only the first point of the following paragraph (92) applied: “The wife receives the name of the husband and enjoys the rights of his estate”. Countess Bertha Kinsky, who was of high nobility on her father’s side, married “down” into a baronial family and was married off. Her family-in-law had also lost some wealth and, above all, social reputation in the stock market crash of 1873. But when she later became famous and used business cards, Bertha always added the words “née [geborene] Kinsky” next to her name, which reflected the importance to emphasise her family connection to the higher nobility throughout her life.

Admittedly, such considerations—as well as the continuation of paragraph 92: “she is bound to follow the husband in his residence, to assist in housekeeping and acquisition to the best of her ability”—did not count for the young couple at first: they had married against the will of the groom’s parents and, therefore, fell out of this social milieu, having no residence in Vienna and hoped, perhaps naively, to find an acquisition in Georgia, of all places, some 3000 km away.

This idea came from Bertha, who twelve years earlier had met Ekaterina Dadiani (1816 – 1882), Princess of Mingrelia, in the days when her mother was still seeking her fortune at the European gambling tables. Acquaintances, especially such interesting and quasi-exotic ones, were cultivated over the years through the exchange of letters and kept warm so to say. Bertha had as little wealth or professional training as her husband, but she could at least activate a social connection. Incredibly, the young couple received an invitation by post.

From a European point of view, Georgia was a legendary country in the Caucasus: for the educated, Mingrelia, the part of the country they arrived in after several weeks of travel, was the home of Medea and the destination of the Greek mythical hero Jason and his Argonauts on their raid for the Golden Fleece. For those interested in politics, the Caucasus was a space where the interests of the Ottoman and Russian Empires clashed. (The Tsarist Russian Empire encompassed the settlement areas of many ethnic groups, including the Georgians, for example, which is why today we speak of the Russian Empire rather than Russia. Russians were the leading political ethnic group, as were the Turks in the Ottoman Empire, which is why this term is incidentally more accurate than the earlier term Turkish Empire; both empires usually emphasised only the leading political ethnic group in their narratives, but their populations were de facto composed of several ethnic groups). Ultimately, the Russian Empire succeeded in maintaining the upper hand in the Caucasus from the eighteenth century onwards and in a kind of internal colonisation expanded its territory partly through wars and partly through political influence. The Suttners experienced one of the last of these wars two years after their arrival in Georgia. Like other colonial empires, the Tsarist Russian Empire also secured its acquisitions by integrating the regional elites into its upper class, which becomes tangible in the example of Niko I. Dadiani (1847 – 1903), the son of Bertha’s acquaintance. He held a leading position in the Tsar’s army and belonged—perhaps nolens volens—to his court society. In Georgia, the Suttner couple first socialised with the princely Dadiani family and with some members of the regional upper class. For some of these, the Suttners were probably exotic people from faraway Europe, which earned them commissions from time to time to give foreign language and music lessons. But there was no question of a regular income, not even when they moved to the capital Tbilisi. They were more like the fortune seekers of all kinds that existed everywhere in colonial outskirts, who wanted to convey their European origins, their languages and their way of life to the local upper class in exchange for hard cash. Since the Suttner couple did not speak the local languages, they lived in a rather narrow “European bubble”, similar to the phenomenon of “expatriates/expats” or “internationals” of our time.

The material situation of the Suttner couple only improved a little when first Arthur Gundaccar began writing for German-language newspapers and so did Bertha too, who soon became far more successful. Many newspapers were founded in the late nineteenth century, which not only commented on politics and economics but also fought to curry favour of the growing reading public through their cultural section. Serialised novels were intended to encourage readers to buy the newspapers regularly, and Bertha von Suttner cleverly catered to this segment. The basis for this was an efficient postal system, which at that time already functioned globally along the trade routes, so that manuscripts reached the editorial offices of German-language newspapers and money transfers, which were urgently needed by the Suttners, reached Georgia in the other direction. Via writing, the therefore established contacts with journalists and writers in Austria-Hungary and the German Reich.

In her memoirs, Bertha describes the time in Georgia as deprived but an idyllic time for a young couple. Her view was to be the only one preserved for posterity; quite deliberately, when she was working on this memoir given that she apparently destroyed letters that had gone to her mother or Arthur’s family. Moreover, her husband died in 1902, which may have been another reason for working on her memoirs. In the fourth part of the memoirs dedicated to the years in the Caucasus, Bertha often refers to her husband as “mine”. However, this was not only a written, retrospective emphasis on feelings, but was also a frequent and peculiar act in the correspondence of Austrian aristocrats of the time to use the cosy form “my man/my lady” even among young married couples.

For Baron and Baroness von Suttner, Georgia was a place of refuge between 1876 and 1885. Their experiences in the Caucasus show, on the one hand, its selective perception by Europeans and, on the other, the increasing integration of this region with Europe.