Part 1: Good to know

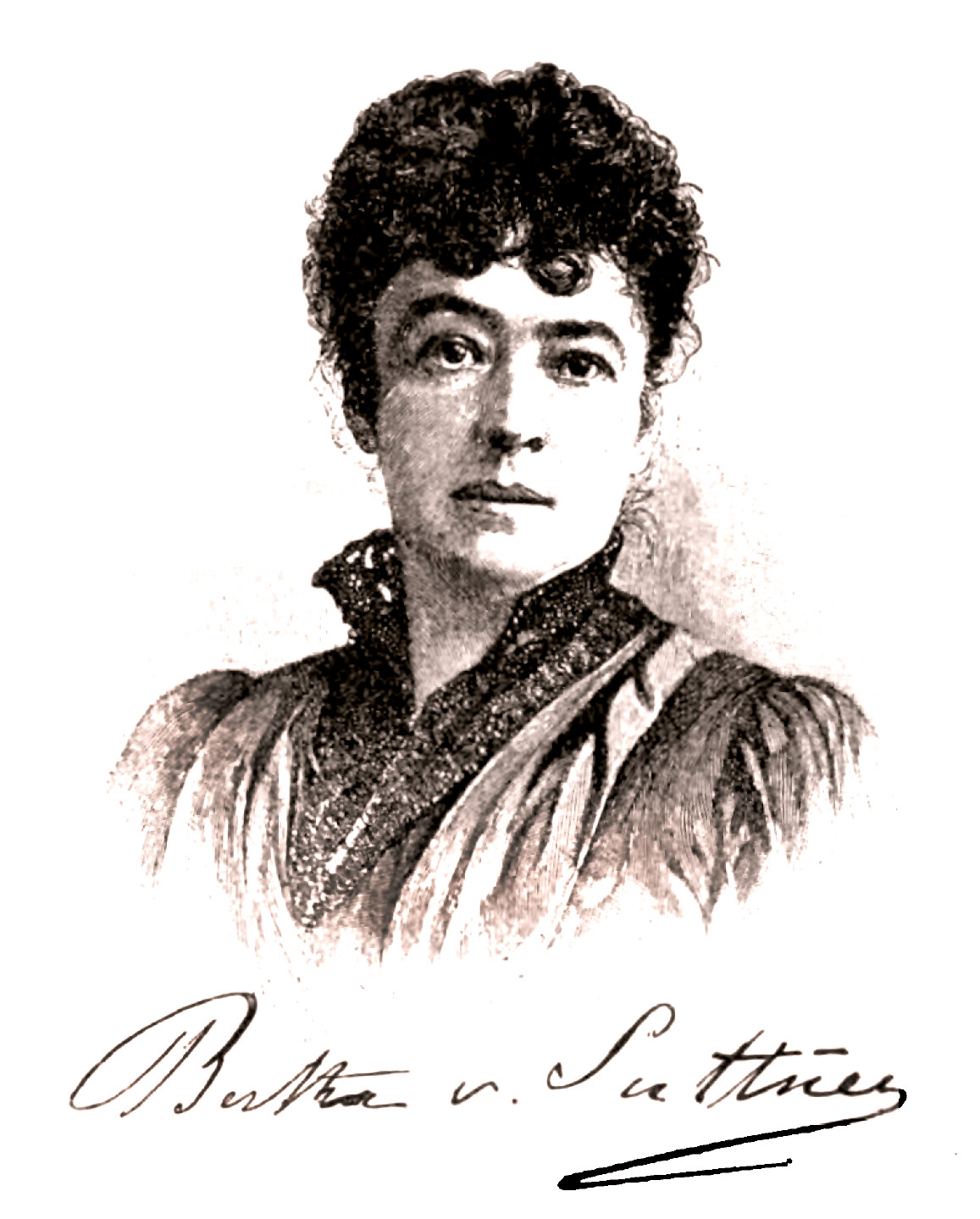

The first book, Dreams Love Flight, is about the childhood and youth of a Bertha von Suttner, who later won the Nobel Prize. As Countess Kinsky, her youthful goal was to marry a rich nobleman. You can find out whether Bertha achieved this by reading Part 1.

You can find the second book Georgia here

What do you learn in this book? Click here for more detailed information…

Bertha von Suttner is best known today as the first Nobel Peace Prize winner. Yet it was her novel Lay Down Your Arms! in 1889 that made her famous beyond the German-speaking world where she had previously earned her living through writing novels and journalistic work. With her newfound ‘world success’, Suttner was able to bring a publication onto the market almost every year as a lecturer and no longer had to knock on publishers’ doors as a beggar. At 64 years old, she wrote her memoirs. This genre also found a wide audience around 1900, but it was still unusual that these memoirs came from a woman as only men who considered themselves and their deeds important published such retrospectives on a successful life. Memoirs by women existed nonetheless, but they had a reputation for being salacious tropes. With her memoirs, however, Bertha von Suttner also wanted to show the development of the peace movement and record her part in it for posterity. In the first of three short parts, she dealt with her childhood, youth and the story of her marriage.

She became cognizant of the interest in her as a person and, as an experienced journalist, she used this to draw attention to her main concern, the peace movement. At the same time, this also gave her the opportunity to critically reflect upon her own part of society.

From her perspective as an experienced and worldly woman, Countess Kinsky judged the high aristocracy of her youth and even wider society through her own experiences, especially as the only goal in life for daughters of all social classes was marriage in order to produce numerous children. Daughters of the aristocracy and upper middle classes were expected to master foreign languages for conversation, but deeper engagement with literature was considered unnecessary and even dangerous. If girls followed their own reading interests or were even interested in science, they were quickly labelled “bluestockings”. Educational in convent schools or through governesses aimed at what most people of the time considered feminine virtues and duties. An assumption of the time, for example, was that women were—by nature—less rational and emotional and so too much intellectual education would stunt their qualities and ultimately endanger supposedly “natural” gender divisions in terms of labour between men and women.

If young women of the nobility and bourgeoisie did not “find a spouse” by a certain age and were “provided by a man” materially through marriage, they did not have an easy lot. Unmarried aristocratic women were, if things went well, provided for by the lord of the manor, i.e. the main heir of an aristocratic house, or entered a Catholic convent (such as those in Innsbruck, Vienna or Prague) or were left with as an old spinster aunt against married siblings. Bertha von Suttner, whose birth as a member of the House of Kinsky was important throughout her life, would not have been entitled to such care. Yet her mother was not a high-born noblewoman—defined as having sixteen noble ancestors within the four preceding generations—and instead came from the noble bourgeoisie. Following her widowhood, she remained unprovided for by the Kinsky family apart from a small inheritance and was “kept” by her husband’s friend who was also the guardian of her children. This relationship was not official around 1850, but everyone would have known this meant that she became his bedfellow despite the fact that he did not want to allow the aristocratic widow into his family house via marriage due to her middle-class origins. Bertha’s mother strove for material independence through the gambling tables of European casinos. Although there were those who counted themselves among the fine society at such institutions—often a mix of rich aspirational people or aristocrats who had fallen off the track as well as artists of all kinds—only the house would win. Such was sadly the case with Bertha’s mother.

Growing up, Bertha was therefore supposed to find a “good match” in a rich man who would take her in and her mother too. Bertha escaped this all too common destiny as her mother relented though the need to find support became more and more urgent. Girls like Bertha lacked suitable vocational training because for her, and women like from aristocratic and bourgeois classes, only had marriage as a means of support. Although women from artisan households had some specialised trade skills and often did the accounts, these talents only increased their value for marriage among bourgeois men. Daughters of civil servants or self-employed academics, on the other hand, received no recognisable vocational training prior to the establishment of teachers’ colleges in 1869. The only option left to them was so-called “bashful work” within their own four walls, i.e. domestic work in homespun clothing (such as embroidery, sewing, and so forth), and also because working in a factory meant social degradation. Bertha had to use her social and human capital for her professional work: with knowledge of foreign languages, singing and piano and a noble background, it should be possible to find a job as a governess! What worked out well in her case and meant she ended up in the Suttner household as was a Europe-wide phenomenon in the 19th century. Although governesses ranked above the domestic servants and dined separately from them with their pupils or even at the table of the house, they were often dependent on the whim of their employer’s family, could be dismissed quickly and were not provided for in case of illness.

The childhood, youth and first occupation of Bertha von Suttner “née Kinsky” can provide insights into female life plans and gender-specific power imbalances that were more common than clichéd stereotypes of the past would suggest.

The recorded texts are taken from Suttner’s memoirs.